Mapping the Mind | Dispatch #2

The mind remains one of science’s final frontiers—complex, unpredictable, and deeply personal. Every few weeks, I gather what’s new, strange, and significant from the expanding edges of neuroscience, psychology, and philosophy.

If you’re drawn to questions about consciousness, free will, and what it means to be a mind, stick around. Subscribe to get the next dispatch straight to your inbox.

These are the latest studies and ideas that stood out 👇

Stoicism, Mindfulness, and the Brain

By Wittmann, Montemayor, and Dorato (link to pdf).

Is free will just an illusion—a trick of the brain that makes us feel in charge when we’re really not? That’s the story told by many popular thinkers today, from Sam Harris to Robert Sapolsky. This new paper pushes back.

The authors argue that real freedom comes from shaping our first-order desires (what we want) using second-order desires (what we want to want), an idea articulated earlier by Harry Frankfurt. Ie: it’s possible to want cake, while also wanting not to want cake. The ability to veto certain desires is sometimes called ‘free won’t’ in comparison to free will.

Our capacity to reflect, evaluate, and redirect our impulses over time eventually shapes us and our desires, and is what the authors see as the heart of free will. It’s a view that echoes Stoic philosophy—where freedom isn’t about spontaneity, but about long-term self-regulation, emotional mastery, and aligning with reason.

But this line of reasoning is likely to fall short of explaining free will for a lot of people—after all, where do those second-order desires come from? Are they not also vulnerable to the same critique as first-order desires—that they, too, might be links in a causal chain, and thus not “free” in the deep sense?

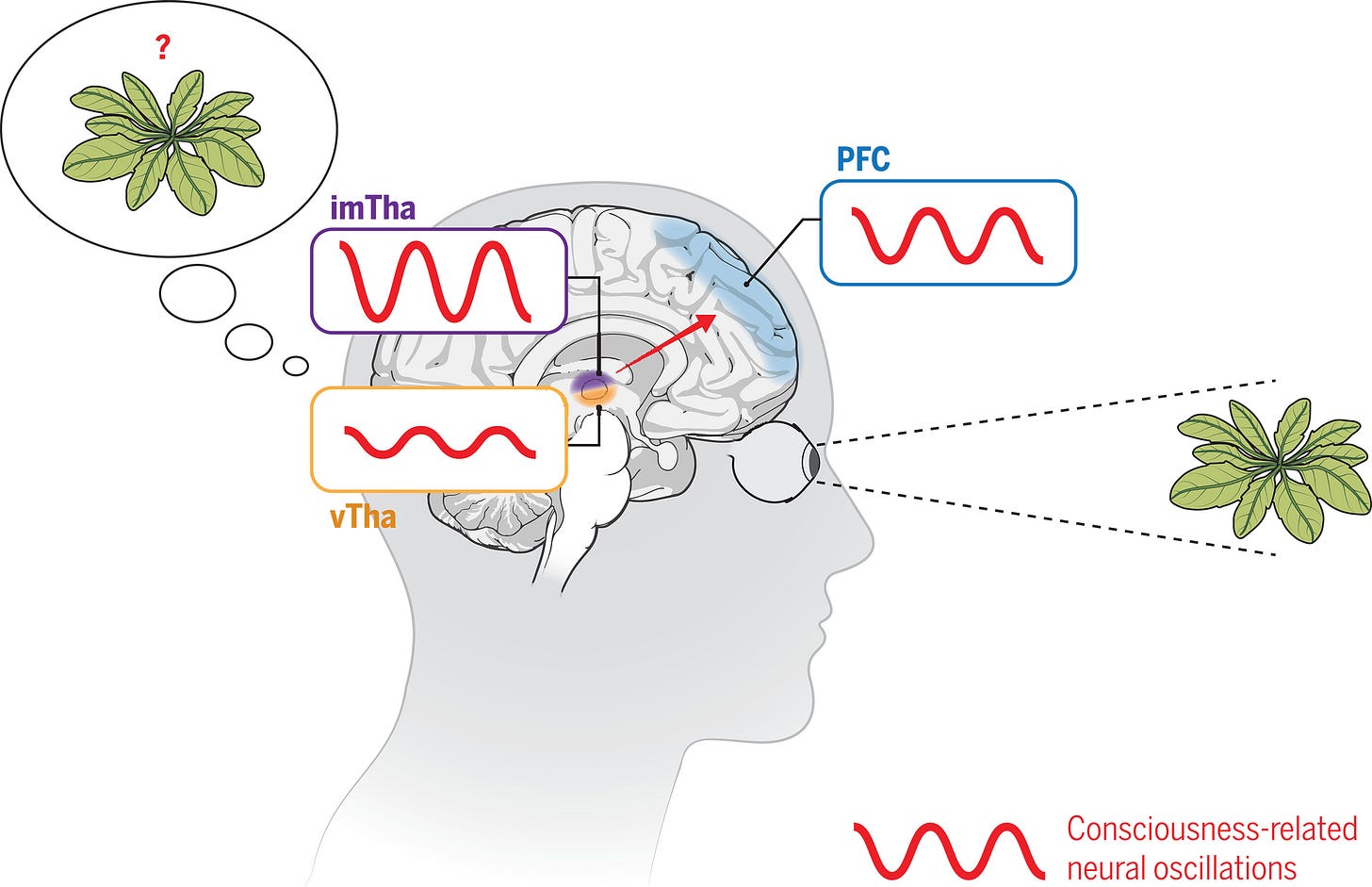

A Gate to Conscious Perception

Human high-order thalamic nuclei gate conscious perception through the thalamofrontal loop, by Fang et al. (preprint pdf, paywalled Science link).

These researchers recorded neural activity from five patients with severe headaches who had electrodes implanted for medical reasons. While these patients performed simple visual tasks, scientists monitored how their brains responded.

They found that two lesser-known regions deep within the brain—the intralaminar and medial thalamic nuclei—were not only involved in visual awareness, but activated earlier and more strongly than the traditionally studied areas. These regions pulsed with low-frequency theta waves (2–8 Hz) just as conscious perception emerged, acting like a rhythm that syncs the brain into awareness.

The study suggests that these subcortical structures, long thought to be passive relays, may in fact play a key “gating” role in what reaches our conscious mind. In doing so, it makes a compelling case that any full understanding of consciousness needs to look beyond the cortex and take subcortical dynamics seriously.

Markers of consciousness in infants: Towards a ‘cluster-based’ approach

This paper explores the controversial and complex question of when consciousness begins in human development. It’s a question riddled with profound ethical implications—the researchers note that until surprisingly recently, infants were often treated without anesthesia because they were not believed to be conscious.

However, identifying and measuring consciousness in adults is hard enough, the difficulties are only compounded in infants who can’t report their experiences or follow instructions, ruling out many of the traditional tests.

The authors argue for using a convergence of different types of evidence, each suggestive of consciousness, to infer its presence. The markers include:

Default Mode Network (DMN) activity

Attentional blink and top-down attention

Multisensory integration (e.g., McGurk effect)

Auditory local-global paradigm (P300 responses)

Taken together, these markers form a “cluster-based” approach—an accumulation of evidence that avoids relying on any single test or theory. While not definitive, their method suggests that “consciousness is likely to be in place by 5 months of age if not earlier.”

Salvaging the “sense of agency”: Metacognitive feelings for flexible behavioral control

By Joshua Shepherd (preprint pdf)

More on the consciousness front. Here, Shepherd addresses a central question in philosophy and cognitive science: what does consciousness contribute to the guidance of action?

Shepherd zeroes in on the sense of agency—the felt experience of initiating and controlling our actions. By unpacking this felt sense of control, he proposes a way to connect conscious experience with the mechanisms of behavioural guidance.

He argues that the sense of agency should be understood as arising from metacognitive feelings that monitor two dimensions of action—action quality (how well the action is going) and action cost (how effortful the action is).

These feelings are central to flexible behavioural control, motivating adjustments in planning, execution, and attention.

“[T]he sense of agency can be fruitfully re-conceived, treated as the product of metacognition, and placed in a promising framework for understanding the flexible control of behavior.”

Perception of a New Colour

Novel color via stimulation of individual photoreceptors at population scale, James Fong et al. (Science link)

By firing lasers at precise cells in subjects eyes, these researchers were able to induce the perception of a novel colour, described as an extremely saturated blue-green, which they’ve named ‘olo’.

The eye has three types of cone cells for colour vision, each one being sensitive to different wavelengths. In normal vision, groups of cells activate together, but using the laser the researchers could isolate particular cells, "which in principle would send a colour signal to the brain that never occurs in natural vision".

Five people took part in the experiment, including co-author Prof Reg Ng, who said olo was "more saturated than any colour that you can see in the real world". The participants rated this as being the closest colour to olo:

Believe What We Think!: The Spinozan Theory of Mind

Draft by Griffin Pion, Elliot Schwartz & Eric Mandelbaum, set to appear in The Oxford Handbook of the Cognitive Science of Belief.

The authors here defend a Spinozan model of belief, which claims that merely entertaining a thought entails believing it to an extent. Only through effortful, secondary processes can we reject or endorse a thought.

This model contrasts with the Cartesian model, which assumes people suspend judgement until they can neutrally contemplate whether to accept or reject it.

Reviewing a range of research, they support the idea that rejecting a belief requires effortful cognition, but when we’re under a high cognitive load these processes are inhibited, causing the persistence of false beliefs.

This might be because we evolved under conditions where immediate acceptance of perceptions was adaptive, while optional rejection developed later in social environments—where language and communication provide a breeding ground for falsehoods.

The psychologist Dan Gilbert studied the same effect, this article discusses his findings.

People are credulous creatures who find it very easy to believe and very difficult to doubt. In fact, believing is so easy, and perhaps so inevitable, that it may be more like involuntary comprehension than it is like rational assessment.

—Dan Gilbert

Get your copy of Free Will

The questions don’t stop here. Explore how thinkers across time have wrestled with freedom, agency, and control in Free Will—the first book in our Collosum collection. It’s available now, and makes a great companion to the themes explored here.

Thanks for reading Collosum! Subscribe for free to receive new posts on the science of mind.